Women under Fire and Siege

Lady Elizabeth Dowdall

On the defence of Kilfenny Castle, co. Limerick in 1642. Apparently she took charge even though her husband was present in the castle at the time. (The 'sows' are cannon.)

The ninth of January, the High Sheriff of the county, and all the power of the county, came with three thousand men to besiege me. They brought two sows and thirty scaling-ladders against me. They wrote many attempting letters to me to yield to them which I answered with contempt and scorn. They were three weeks and four days besieging me before they could bring these sows to me, being building of them all that time upon my own land, yet every day and night in fight with me. The Thursday before Ash Wednesday, High-Sheriff, Richard Stephenson, came up in the front of the army, with his drums and pipers, but I sent him a shot in the head that made him bid the world goodbye, and routed the whole army, we shot so hot... On Thursday, they drew their sows nearer, and Friday, they came on, at night with a full career and a great acclamation of joy, even hard to the castle. But I sent such a free welcome to them, that turned their mirth into moaning. I shot iron bullets that pierced through their sows, though they were lined with iron gridds and flock-beds, and bolsters, so that I killed their pigs, and by the enemy's confession that night two hundred of their men.1

Defence of Wardour Castle by Lady Arundel, 1643, detail from 'Mercurius Rusticus'

Magdalen Faulkner

Writing from Ireland following the Catholic rising in Munster, in March 1642. The reports of Catholic atrocities against Protestants were largely exaggerated propaganda - but Magdalen's fears are very real.

We are here in a most pitiful and lamentable case as ever poor people were in. God help us, we have and hear of nothing but fire and the sword and pitiful sights of poor people stripped naked as ever they were borne and we can expect nothing but famine for they destroy all - they which at Michaelmas last were worth three or four thousand pounds now begs at our door. My Lord behaves himself gallantly in this business for we have fifty family in our houses for safety, and four times as many in our other castle, and none of my lords own country is yet in rebellion, but we fear them every day and look to be besieged and our town fired, for the enemy takes our cows and cattle to our very door God help us we know not what to do.

We are fled from our own house, for the enemy came with so great a number against us, that my Lord durst not let my lady and the children stay. I think the next remove will be into England, for the enemy pursues us everywhere and vows our death, because we will not go to mass which God Almighty keep us from. 2

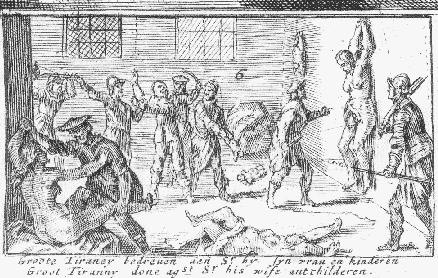

Irish atrocities against protestants, Dutch propaganda print

Doll Leeke

In the Royalist army camp, September 1642, writing of the fears and discomforts endured there.

For my confidence of our having the better of the parliament I do not remember, but if they will promise to fight no better it will strengthen my hopes; but I cannot see if we have the better how you will suffer, for sure your father will have power to save your husband, and if the King fail I believe my uncle will hardly come off with his life or any that are with them; therefore your condition is not so bad as you believe it, at least I conceive so. I think none in more danger than myself and our company, for if we lose the day, what will become of us I know not. We do not look for any favour of the other side. I do not love to think of it and I trust I shall not live to see it. Part of our trouble now is that the weather grows cold and it will be ill travelling, and we have [left] those things which should have kept us warm at Yorke; but by that time we have followed the camp another year we shall have more wit. 3

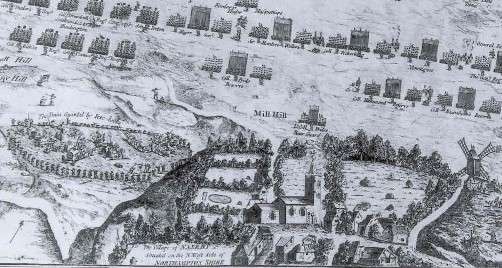

In the shadow of battle: the village of Naseby and the baggage train, detail from a contemporary plan of the battle, 1645

Queen Henrietta Maria

Writing to Charles I about coming under bombardment at Bridlington, in February 1643, after landing there with arms and ammunition from Holland for the royalist cause.

God, who took care of me at sea, was pleased to continue his protection by land. For that night four of the Parliament's ships arrived at Bridlington without our knowledge and in the morning, about four o'clock, the alarm was given that we should send down to the harbour to secure our ammunition. But about an hour after these four ships began so furious a cannonading that they made us get out of our beds and quit the village to them - at least us women, for the soldiers behaved very resolutely in protecting the ammunition... One of these ships did me the favour to flank my house, which fronted the pier, and before I was out of bed the balls whistled over me; and you may imagine I did not like the music. Dressed as I could, I went on foot some distance from the village, and got shelter in a ditch, like those we have seen about Newmarket. But before I could reach it the balls sang merrily over our heads and a sergeant was twenty paces from me. Under this shelter we remained two hours, the bullets flying over us, and sometimes covering us with earth. At last the Dutch admiral sent to tell them that if they did not cases he would fire upon them as enemies. This was a little late, but the admiral excused himself because of a fog which he said was there. On this the Parliament ships went off, and if they had not done so then the ebbing tide would have left them in shoal water. As soon as they were retired I ventured back to my house, not choosing that they should have the vanity to say they had made me quit the village.4

Henrietta and Charles I, portrait by Anthony van Dyck

Alice Thornton

Writing of events of July 1643, when she was caught in a siege at Chester and providentially 'delivered' from harm

But I had in this time of the siege a grand deliverance, standing in a turret in my mother's house, having been at prayer in the first morning, we were beset in the town; and not hearing of it before, as I looked out at a window towards St. Marie's Church, a cannon bullet flew so nigh the place where I stood that the window suddenly shut with such a force the whole turret shook; and it pleased God I escaped without more harm, save that the waft took my breath from me for that present, and caused a great fear and trembling, not knowing from whence it came.5

'A great and bloody fight at Colchester', contemporary broadsheet narrating the siege at Colchester, 1648

Brilliana Harley

From a letter to her son Edward at the beginning of the (long-anticipated) siege of Brampton Bryan Castle, August 1643. Brilliana was a reluctant 'heroine', very different from Elizabeth Dowdall; throughout the siege, she claimed that she was doing only what her husband would have wished her to do.

Now, my dear Ned, the gentlemen of this country have affected their desires in bringing an army against me. What spoils has been done, this bearer will tell you. Sir William Vavasor has left Mr Lingen with the soldiers. The Lord in mercy preserve me, that I fall not into their hands. My dear Ned, I believe you wish yourself with me; and I long to hear of you, who are my great comfort in this life. The Lord in mercy bless you and give me the comfort of seeing you and your brother... Mr Phillips has taken a great deal of pains and is full of courage, and so is all in my house, with honest Mr Petter and good Doctor Wright and Mr Moore, who is much comfort to me. The Lord direct me what to do; and, dear Ned, pray for me that the Lord in mercy may preserve me from my cruel and blood thirsty enemies. 6

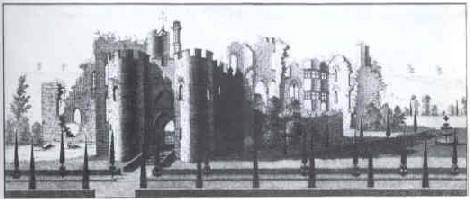

Brampton Bryan in ruins, early eighteenth-century print

Ann Fanshawe

Writing in her memoirs of more upheavals in Ireland, 1649.

We remained some time behind in Ireland, until my husband could receive his Majesty's command how to dispose of himself. During this time I had, by a fall of a stumbling horse, being with child, broke my left wrist, which because it was ill set, put me to great and long pain; and I was in my bed when Cork revolted. By chance my husband that day was gone upon business to Kinsale. It was in the beginning of [Octo]ber 16[49], at midnight, I heard the great guns go off, and thereupon I called my family to rise; which they and I did as well as I could in that condition. Hearing lamentable shrieks of men and women and children, I asked at a window the cause. They told me they were all Irish, stripped and wounded, turned out of the town; and that Colonel Jeffries, with some others, had possessed themselves of the town for Cromwell. Upon this I immediately wrote a letter to my husband, blessing God's providence that he was not there with me, persuading him to patience and hope that I should get safely out of the town by God's assistance; and desired him to shift for himself for fear of a surprise, with promise I would secure his papers. So soon as I had finished my letter, I sent it by a faithful servant, who was let down the garden wall of Red Abbey, and, sheltered by the darkness of the night, he made his escape. Immediately I packed up my husband's cabinet, with all his writings, and near £1000 in gold and silver, and all other things, both of clothes, linen, and household stuff, that were portable and of value. And then, about three o'clock in the morning, by the light of a taper, and in that pain I was in, I went into the market-place with only a man and maid; and passing through an unruly tumult, with their swords in their hands, searched for their chief commander Jeffries, who whilst he was loyal had received many civilities from your father. I told him that it was necessary that upon that change I should remove, and desired his pass that would be obeyed, or else I must remain there. I hoped he would not deny me that kindness. He instantly wrote me a pass both for myself, family and goods, and said he would never forget the respects he owed your father. With this I came through thousands of naked swords to Red Abbey, and hired the next neighbour's cart, which carried all that I could remove; and myself, sister, and little girl Nan, with three maids and two men, set forth at five o'clock in [Octo]ber, having but two horses amongst us all, which we rode on by turns. In this sad condition I left Red Abbey, with as many goods as was worth three hundred pounds, which could not be removed, and so were plundered. We went ten miles to Kinsale in perpetual fear of being fetched back again; but by little and little, I thank God, we got safe to the garrison, where I found your father the most disconsolate man in the world, for fear of his family, which he had no possibility to assist. But his joys exceeded to see me and his darling daughter, and to hear the wonderful escape we through the assistance of God had made. 7

Quoted in O'Dowd, 'Women and war in Ireland', 93. ↩

Magdalen Faulkner to Ralph Verney, 8 and 17 March 1642. Memoirs of the Verney family, I, 236. ↩

Doll Leeke to Lady Verney, 1 September 1642. Memoirs of the Verney family, I, 260. ↩

Henrietta Maria to Charles I, 25 February 1643. Quoted in Adair, By the sword divided, 133-34. ↩

Jackson (ed), Autobiography of Mrs Alice Thornton, 33. ↩

Brilliana Harley to Edward Harley, 25 August 1643. Lewis (ed), Letters of Lady Brilliana Harley, 207-8. ↩

Fanshawe (ed), Memoirs of Ann, lady Fanshawe, 53-55. ↩